Piers Taylor was asked by Common Ground to contribute a chapter to a new anthology on personal experiences of woodland that is being published in memory of Oliver Rackham. Here is the text:

It is mid May, and I am surrounded by iridescent lime green beech trees, heavy after the rain with shimmering – even effervescent – wild garlic bursting into flower underneath. The trees, plants and sheer visceral actuality of the stuff around me – and its seasonal abundance – remind me that woodland is our natural state in the UK, and that everything here reverts to woodland if left alone. This makes it hard to remember that globally, we are living through the greatest rate of social change in the history of human kind, where, at an unprecedented rate, we are becoming urbanized, abandoning the countryside for the city, seemingly unconcerned with the bucolic.

Such is the dominance in the arts of the metropolitan, that for an early part of my working life, I felt a kind of guilt that my own work was so focused around the rural – and questioned even the validity of making work that was concerned with matters that did not address the overriding architectural concern of our age: how to live sustainably in dense, urban environments. As an architect, I often find myself on the fringes as a reluctant agent of cultivation.

Although for periods of my life I have lived in the city, growing up, landscape and nature were woven in to the fabric of my life, inseparable from the day to day – and this intrinsic and fundamental relationship with the natural world stemmed from my upbringing. As children, we grew up with a small woodland on my parents’ land, and in our mid teens, my brother and I would spend much of our time thinning the woodland, felling trees and splitting wood. In our later teens, my parents bought a remote Welsh house two miles from the nearest road and with no electricity, where we spent most weekends and much of our holidays.

My father would always know instinctively and precisely how the daylight patterns of sunrise and sunset differed from the day before and the day after. He’d be the first to spot the subtle changes in colour in winter as, way before there were any buds, branches would become slightly pinker in preparation for spring. He would always know when the first snowdrop appeared, and how it differed from all of the previous years, where the first nightingale would be singing, and how in spring the brightness of the green elm flowers differed from year to year.

My father was (is still, at 87) always an obsessive naturalist. He had grown up as part of a generation that made an exodus the countryside during WW2, and as part of a family with a single working mother and four children, they ran semi wild in the Cumbrian landscape to which they had escaped. As a teenager, he’d think nothing of cycling the full length of the country bird watching, sleeping under hedges as he went. This desire to explore meant that he became part of the British Antarctic Survey Expedition in the 1950s (immortalized in W Ellery Anderson’s 1957 book ‘Expedition South’), where, dressed in tweeds, he spent three years sledging with a pack of huskies, surveying glaciers and designing the first optimized dogs diet.

Landscape, nature, the countryside – all of this, as a wider family, was part of who we were – but I’d never really made the connection with architecture until my first week of University. I’d been a wayward child and had been repeatedly expelled from school – for being considered ‘un-teachable’ (read energetic, curious and distrusting of authority) – and had wound up in Sydney (my mother’s homeland) and entered university on the strength of a portfolio (I had no formal A levels) to study design.

In the first semester, all design students were taught together alongside architecture students – and consequently shared lectures. The first lecture in the first was by an architect – Glenn Murcutt – who gave me a road map for most things I’ve done in the 25 years since then, and I came out of the lecture, reeling, my head spinning with the possibilities I’d been shown by Murcutt, and went immediately to the university office and transferred to architecture.

Murcutt talked of geomorphology, geology, hydrology, topography, flora fauna, and the imperatives of understanding weather patterns and climate as intrinsic to architecture. He talked of how farmers and rural dwellers knew characteristically how to orientate a building to keep the rain out, and how to maximise ventilation to moderate climate. He demonstrated how to use scarce resources effectively. He talked of the fragility of landscape and how to build without disturbing a site. And, he showed me how you could define an architecture by examining a place – critically, an architecture that was distinct from place, but was utterly defined by it.

Murcutt talked of geomorphology, geology, hydrology, topography, flora fauna, and the imperatives of understanding weather patterns and climate as intrinsic to architecture. He talked of how farmers and rural dwellers knew characteristically how to orientate a building to keep the rain out, and how to maximise ventilation to moderate climate. He demonstrated how to use scarce resources effectively. He talked of the fragility of landscape and how to build without disturbing a site. And, he showed me how you could define an architecture by examining a place – critically, an architecture that was distinct from place, but was utterly defined by it.

Murcutt’s work was also quintessentially and effortlessly Australian, and presented such an incredibly powerful narrative about place. His modest, frugal, delicate structures were so totally bound up in the specifics of site – and yet spoke of universal themes about climate, belonging and culture. Conventional modernism had banished regional concerns, but Murcutt showed how the particular, the regional and the local were themes that could have centre stage in a new architecture. As legendary British architect Alison Smithson said, “Murcutt found an exquisite architectural poetry in sunlight and rainwater collection and harnessing the natural environment.”

Fast-forward ten years or so, and, back in the UK, I was practicing in the south west of the UK and teaching architecture at the Universities of Bath and Cambridge. What was becoming apparent to me was – in architecture – the divisive split between ‘thinking’ and ‘making’. What I hadn’t understood at the time was how timber – or trees – would help me bridge the gap with my own practice and teaching work.

In 2002 I’d bought with my partner a 200-year-old tiny stone castellated building in the middle of a woodland (traditionally called Moonshine Wood) on valley-side 5 miles form Bath that was inaccessible except on foot via a 500 metre path. I’d fallen in love with the site when Sue was in hospital having our second child, and was gripped by a primaeval need to be in that woodland. The old building was habitable (just) and came with about half an acre of land.

Immediately, woodland became a way of life for us – it completely surrounded us and the rhythms of the woodland became, to a degree our own rhythms. The woodland rhythms were those of the bluebells, the goshawks, the fungi, the badgers, the wild garlic, the orchids and the gradual closing in of the woodland each May, which, living so immersed in the woods, threatened to envelop us completely. What we were so graphically exposed to was the way that woods work. Woodland ceased to become an abstract entity, and instead we saw them as – as Richard Mabey described in Beechcomings, as “symbiotic networks of carpenters, beetles, deer, land-thieves, lichens, pollards and toadstools” and, critically for us, our home.

A love affair with timber itself began when we built a new house on the site, next to the old stone folly. The house was conceived of as a structure that – using Murcutt’s own phrase – touched the ground lightly. It was raised off the ground, leaving the highly shrinkable clay and the water table around the house undisturbed.

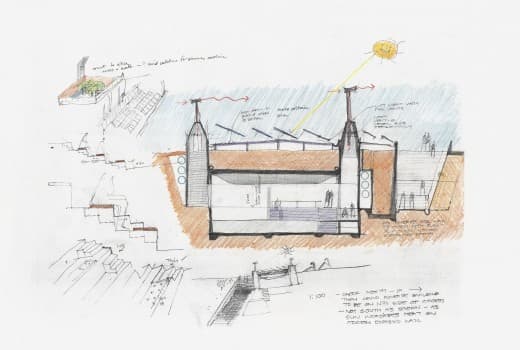

The house in Moonshine Wood was designed to maximize early morning and winter sunshine, and took its form from an analysis of wind and weather patterns in the valley. Having lived on the site for two years helped enormously. One of my teachers, Richard Leplastrier, described how he get to know a place, prior to designing: “For many buildings I have camped on site, many days and nights, with a drawing board. It is the best way to feel a place out. The form of the terrain, its effect on climate, the path of animals and the sun. Where do you put your campfire?” Using Leplastier’s analogy, we felt ready to know where to put our campfire.

The house had to be designed to be carried in components along the woodland track and so inevitably using timber made sense, as it is so ready a material that allows – encourages, even – on-site improvisation. Curiously, though, I’d had little experience of working with timber. It was a material that the architectural world had become suspicious of – given its relative unpredictability and its refusal to act submissively.

Working on my own house – physically constructing it myself – exposed to me my own naivety in terms of preconceptions around the idea and ideal of the drawing being a mechanism of control. In architecture, instead of drawing being a tool for thinking or discovery, it has become a ‘command’ whose purpose is to banish contingency, uncertainty, or on site discovery.

Working on my own house – physically constructing it myself – exposed to me my own naivety in terms of preconceptions around the idea and ideal of the drawing being a mechanism of control. In architecture, instead of drawing being a tool for thinking or discovery, it has become a ‘command’ whose purpose is to banish contingency, uncertainty, or on site discovery.

Historically, it was drawing- as opposed to building – that affirmed the status and idea of the architect as an individual mostly concerned with immaterial ideas. The architect produces a set of instructions – drawings – which fixes outcome and ensures that a singular vision is exactly realized by anonymous construction workers who are concerned with material (and subservient) ideas. Indeed, the prevailing condition in architecture is one where the hand – and judgment – of the maker is banished.

Building my house, and using timber, gave me a glimpse of the extraordinary richness of the material world, and how more than anything, I was missing out on a world of visceral and sensual feedback – not just from the material itself, but also from the sheer potential and excitement that was exposed once ‘making ‘ and the collaborative conversation with all involved in making – was expanded to encompass designing – and the real time uncertainties were brought centre stage in stead of being banished. Looking back now, the evolution of my way of thinking about making stemmed from this period of building my own house, and how It opened my eyes to a sense of what the process of construction and material exploration could offer.

What followed was an about turn in my method of teaching, and the same year that I built the house a group of us started something we called ‘Studio in the Woods’. We didn’t ‘set it up’ – I’m suspicious of things that are ‘set up’ or premeditated too much – Studio in the Woods just evolved out of friendships with other architects, and casual conversations about how it could be fun to organise a workshop with students in the woods around my house. Trusting we’d be agile enough to catch things as they happened, we just threw the cards up in the air to see where they landed.

Where they landed – or what came out of the first weekend of Studio in the Woods 10 years ago – set the pattern for subsequent years. We’d test ambitious ideas quickly, at 1:1, using timber felled and milled on site. For me, the giddy and heady freedom that came with being able to work directly, with materials to hand and with the chaos and surprise of inventing on the hoof was amazing.

This way of working allows the richness of discovery, conversation and contingency to be incorporated in real time into the architecture. The anthropologist Tim Ingold calls this ‘a way of knowing from the inside – a correspondence between mindful attention and lively materials conducted by skilled hands at the [material’s] edge’.

This is a way of working that I’ve been moving towards for 15 years now. Underpinning this move towards a different way of working is a fascination in using full scale making as a method of testing ideas, and using the process of consolidation or accumulation as a design tool. Rather than refining a prototype and then unveiling something perfectly formed and defect free, I am interested in allowing a prototype to be continuously modified and adapted so that it is allowed to become the ‘final’ piece, with modifications and mistakes made manifest.

This is a way of working that I’ve been moving towards for 15 years now. Underpinning this move towards a different way of working is a fascination in using full scale making as a method of testing ideas, and using the process of consolidation or accumulation as a design tool. Rather than refining a prototype and then unveiling something perfectly formed and defect free, I am interested in allowing a prototype to be continuously modified and adapted so that it is allowed to become the ‘final’ piece, with modifications and mistakes made manifest.

Studio in the Woods provided me with this new model of working – one where new architectural forms and relationships could be discovered, rather than merely willed. One of the big questions many architects have is – if we don’t merely want to use precedent or deterministic processes, how do we discover architectural form? For me, allowing construction, material exploration and full scale making in real time went some way to answering this.

In addition, it provided a freedom from a world where only ‘skilled’ people could make things. The material relationships that are formed by alternatively-skilled (conventionally unskilled) people are often more interesting to me than those that are perfectly, and blindly, crafted. I’m a big fan of the ‘bodged’ joint where evidenced in it is the maker’s journey of discovery. Of course the ‘bodger’, instead of being a cack-handed and clumsy labourer, was traditionally an itinerant worker who used green timber and found materials that led to unconventional timber joints and connections.

Architecture is, or was, full of concern with ‘correct’ detail and material expression. The Fall’s Mark E Smith called Rock ‘n Roll the ‘mistreating of instruments to explore feelings’, but in architecture, even at its most loose and improvised, there has conventionally been little room for mistreating of tools to explore ideas – or buildings made by ‘amateurs’ or ‘bodgers’ without due regard for technique. My buildings are often badly made in the received sense and often have little regard for technique. This doesn’t mean I don’t care about how they are made. On the contrary, I care enormously about how they are made and the elemental relationships between components, but these relationships differ from those held sacrosanct by high architecture.

What emerged from my work with Studio in the woods was an invitation from London’s Architectural Association to get involved with establishing a new program for students in a 400 acre woodland in rural Dorset, which had been bequeathed to them by the furniture designer John Makepeace. He had established the woodland as a research facility which examined how low grade forest thinnings could be used in construction. Several seminal structures had been built there including Frei Otto’s building that used young waste wood in the construction of a lightly skinned big workshop.

The AA’s idea was to set up a new masters programme where, over 16 months, architecture students would design and construct their own campus using timber sourced from the Hooke woodland. The first building that came out of the program was a complex and unusual big span workshop that used juvenile larch between 12 and 18 years old. My role developed from tutor into executive architect, and, with the engineers Atelier 1 and carpenter extraordinaire Charley Brentnall, we developed a system of using standard 300mm house-builders fixings to connect the timbers – a low tech, low skill method that allowed students and volunteers to assemble the building alongside Brentnall’s skilled team.

The AA’s idea was to set up a new masters programme where, over 16 months, architecture students would design and construct their own campus using timber sourced from the Hooke woodland. The first building that came out of the program was a complex and unusual big span workshop that used juvenile larch between 12 and 18 years old. My role developed from tutor into executive architect, and, with the engineers Atelier 1 and carpenter extraordinaire Charley Brentnall, we developed a system of using standard 300mm house-builders fixings to connect the timbers – a low tech, low skill method that allowed students and volunteers to assemble the building alongside Brentnall’s skilled team.

What followed was a series of buildings and structures forming the campus using almost exclusively materials sourced from the woodland at Hooke, with teams formed from a combination of those who were conventionally skilled alongside those who were unskilled in construction.

What followed was a series of buildings and structures forming the campus using almost exclusively materials sourced from the woodland at Hooke, with teams formed from a combination of those who were conventionally skilled alongside those who were unskilled in construction.

Inspired by an impromptu ad hoc coming together of interesting people at Hooke Park and Studio in the Woods, I realized that there was no room in conventional practice for me. I resigned from the practice that I’d co-founded (Mitchell Taylor Workshop) and formed Invisible Studio to allow a method of practice that made more sense to me.

Invisible Studio took its template from Studio in the Woods where there was no institution, no one owned it, no organisation funded it, no one audited it, and it was beholden to no one. There was never any commitment to ever work together again. There was no hierarchy, no presumptions and certainly no succession planning. Studio in the Woods wasn’t a charity, a company or a co-op – and nor is Invisible Studio. Like Studio in the woods, Invisible Studio isn’t a practice – it’s a kind of anti-practice. It is just people, who work together with no labels, titles or expectation. It has no fixed work force, no formal company – it is just a loose, unstructured collection of people who work together when the conditions are right, and don’t when they aren’t. The simple motivation is the creative work. Alongside this, the world of timber has become more and more fascinating to me. We’ve recently bought – with our neighbours – the 100 acre woodland around the house, which we manage alongside practice and family life and built our studio in it with timber from the woodland, using friends, neighbours and bodgers in its construction, and almost no drawings.

The studio was an exercise in harnessing the resourcefulness that many of my rural neighbours have. Few had any formal construction knowledge, and certainly none had ever built a building before. Free from the baggage of ‘correct’ ways of doing things, all brought an extraordinary sensibility to the project. The building was an exercise in frugality that is typical of many traditional rural buildings – we simply used local materials and resources to shape the project. In an era where most architecture is defined by its extravagance, the studio was an attempt to do the most with the least.

The studio was an exercise in harnessing the resourcefulness that many of my rural neighbours have. Few had any formal construction knowledge, and certainly none had ever built a building before. Free from the baggage of ‘correct’ ways of doing things, all brought an extraordinary sensibility to the project. The building was an exercise in frugality that is typical of many traditional rural buildings – we simply used local materials and resources to shape the project. In an era where most architecture is defined by its extravagance, the studio was an attempt to do the most with the least.

Working in this vein, we have now just finished delivering two buildings for Westonbirt, the National Arboretum, that forms their Tree Management Centre using a similar method, but with a completely different scale. The buildings are the first that the arboretum have built using their own timber – and use 20 metre long hand hewn Corsican Pine structural members in complete lengths – as well as Oak, Spruce, Larch and Douglas Fir. Many volunteers have worked on the project alongside skilled carpenters, and the Carpenter’s Fellowship have used the buildings as vehicles for up-skilling their trainees.

Living in a woodland, working with timber in this manner and embracing contingency, chance and the glorious properties of green timber felled on site as part of a wider management plan, architecture for me has shifted immeasurably away from the idea of a lone designer, working on a static object of singular, finite and shallow beauty. Design has becomes a forum that allow the unexpected to emerge. The architectural academic Jeremy Till, who is highly critical of much contemporary practice describes this way of working as a ‘crucible for exchange between a mix of professionals, amateurs, dreamers and pragmatists’ with the architect an ‘open-minded listener and fleet-footed interpreter, collaborating in the realization of other people’s unpolished visions’. For me now, it is among these amateurs, dreamers, pragmatists, bodgers and – perhaps most importantly, trees – that I thrive, in the knowledge that all of my own work will, one day, revert to the woodland matter from where it came.

Living in a woodland, working with timber in this manner and embracing contingency, chance and the glorious properties of green timber felled on site as part of a wider management plan, architecture for me has shifted immeasurably away from the idea of a lone designer, working on a static object of singular, finite and shallow beauty. Design has becomes a forum that allow the unexpected to emerge. The architectural academic Jeremy Till, who is highly critical of much contemporary practice describes this way of working as a ‘crucible for exchange between a mix of professionals, amateurs, dreamers and pragmatists’ with the architect an ‘open-minded listener and fleet-footed interpreter, collaborating in the realization of other people’s unpolished visions’. For me now, it is among these amateurs, dreamers, pragmatists, bodgers and – perhaps most importantly, trees – that I thrive, in the knowledge that all of my own work will, one day, revert to the woodland matter from where it came.

Piers Taylor © 2016

I’ve been wondering recently why as a country, we’re all so desperately conservative when it comes to our domestic buildings. I don’t mean in terms of tradition, taste or style – but in the way that the building works.

I’ve been wondering recently why as a country, we’re all so desperately conservative when it comes to our domestic buildings. I don’t mean in terms of tradition, taste or style – but in the way that the building works.